An Overview

A Stream: Near Beauvais (1860-70), detail

Today I’m delighted to share with y’all some inspirational info about Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875). Corot was a prolific landscape artist. Like many landscape painters in his time, he travelled often and worked among other painters. (At times he invited other artists to complete sections of his work. Check out Zuydcoote Near Dunkirk by Corot, Daubigny and Oudinot to see three different styles in one piece). Collaborative paintings fell out of favor as the Impressionist movement (and its emphasis on originality) gained momentum and single-artist works grew in favor.

It was common practice for landscape artists of this era to develop and hone their techniques for capturing a scene by working through several studies. Studies such as these were completed en plein air alongside the artist’s close observations of nature and were invaluable in helping artists plan and finish paintings from memory later on in the studio. The detail that these masters achieved with the oils on their canvases required patience with the lengthy process of layering textures and colors. Artists’ carefully rendered field-studies allowed them to capture the luminous lights and colors of the natural landscapes while working over a longer length of time in the studio later on.

Although such studies were never meant for exhibition, some of Corot’s early Italian studies became known as some of his greatest achievements after his death. The power of studying one’s subject closely and producing several studies in order to become better acquainted with the subject cannot be underestimated. Here is a lovely excerpt from one of the placards at the Frye Art Museum exhibit (in reference to Souvenir of Lake Albano, which I have not been able to find reference to online since, so I wonder if I wrote it down incorrectly. Yet still, the beautiful expression of how he approached his craft is worth sharing):

Rather than conjuring an imaginary Italianate landscape from the time of antiquity as his teachers of the Neoclassical school would have done, Corot evokes a more romantic quality, suffusing [the painting] with a silvery light and an emotional resonance based on his own subjective experience of the site.

The Lake: Night Effect (1869), detail

These opposite approaches to landscapes fascinate me. The neoclassicists would ‘conjure up an imaginary… landscape… from antiquity’ and produce a more realistically rendered landscape setting in their finished piece. Conversely, Corot (as a Realist, Romantic and predecessor of the growing Impressionist movement) would spend time with a particular place, soaking it up, learning how it looked in all manner of changing light, and complete many studies en plein air to assist him in his work back in the studio. But the purpose of completing studies to inform the final painting were never about capturing the accuracy of the moment alone, but moreso the feel of it. While the neoclassicists were interested in using landscapes as a backdrop for their prosaic paintings (insisting on including characters from well-known tales so as to legitimize the need for painting a landscape), the Realists, Romantics and later the Impressionists were seeking to capture the feel and experience of a place itself and for the place to take center stage as the subject of their poetic brush strokes.

As Corot entered the last quarter of his life, his approach shifted somewhat and he exhibited nearly 30 paintings with titles beginning with souvenir, which means recollection or remembrance. These paintings were completed mostly from memory and are akin to lyrical interpretations of his senses of the places themselves. It seems so next-level to me. After years of spending time soaking in these places during his extended time there, he painted them without the need for any additional preparation or study. He had assimilated them into himself so completely that he could paint their soul straight from his own.

Takeaways

There’s much for us to glean from Corot’s working life. Here are the things I want to remember to integrate more into my own artistic practice. I invite you to do the same!

Corot understood the value of community. He surrounded himself with other artists and enjoyed collaborating with his friends. He wasn’t afraid to invite them to add some of their own style and creativity to his own pieces. - Where are there opportunities for us to connect with and collaborate with other creative folk? How can we let people in to our creative experience?

He spent time studying each place. To my thinking, the completion of studies to later use as reference materials isn’t at all the point. The significance of this practice is the time spent making the studies themselves. Imagine, spending time with a place through the changing light of each day, through shifts in weather, and the turning of seasons. The practice of completing studies helped him see the place more fully and integrate it more deeply within himself while also helping him work out complex plans and strategies for executing the eventual final piece. - What one place or object can we commit to spending time with and really getting to know? Can we give ourselves permission to work through study after study and let the focus be on the process itself? Can we sit with something that we care about, diligently practice our craft, and simultaneously work out both our relationship [with the subject] and our technical skill without fixating on a final finished-piece throughout?

He understood that there’s more than one way to portray a subject and that the Neoclassical way that he was trained wasn’t the style that resonated with him. - Spending time soaking up our subjects does not necessitate stressing about conveying visual realism. We also don’t have to provide any justification to make our beloved subjects somehow worthy in the eyes of others. Let’s be kind to ourselves, nurture a strong relationship with a subject that really matters to us, and then portray our beloveds in our own unique style. Let’s shift our focus from perfectionism and fix our eyes instead on the essence, feel, and spirit that we want to convey instead of getting bogged down in the perceived technicalities of our craft. (Is it possible that those technicalities will begin to sort themselves out naturally as we spend time creating study after study as a means of getting to know our dear muse? I think so.)

Time spent nurturing relationship is never wasted. All the memories of cherished places that he assimilated into himself throughout his life grew to become the loose, poetic, dreamy work of his later years. - If no particular muse is calling to us now in our present moment, certainly there is some cherished memory lodged within each of us that might like to dance upon our pages?

A Path Under the Trees in Spring (1860-70), detail

In answer to those reflective questions above, here are the goals I’m setting for myself in the spirit of learning from Corot:

I will work on opening myself up to creative community a little more, which I admit I’m sometimes slow to do because of my own insecurities. This will be a work in progress for me.

Because I’m traveling and my scenery is ever changing, I will look for a portable muse that I can really spend time with and get to know. Honestly, I have no idea what that might be, but I’ll be on the lookout for something worthy of the kind of devotion that Corot gave to the places he painted. Then, I will emphasize spending time with my muse and completing studies for the purpose of knowing them better, not for the purpose of creating a finished piece. By emphasizing this shift in perspective I will work to avoid the pitfall of stressing about my technique or perceived lack of skill.

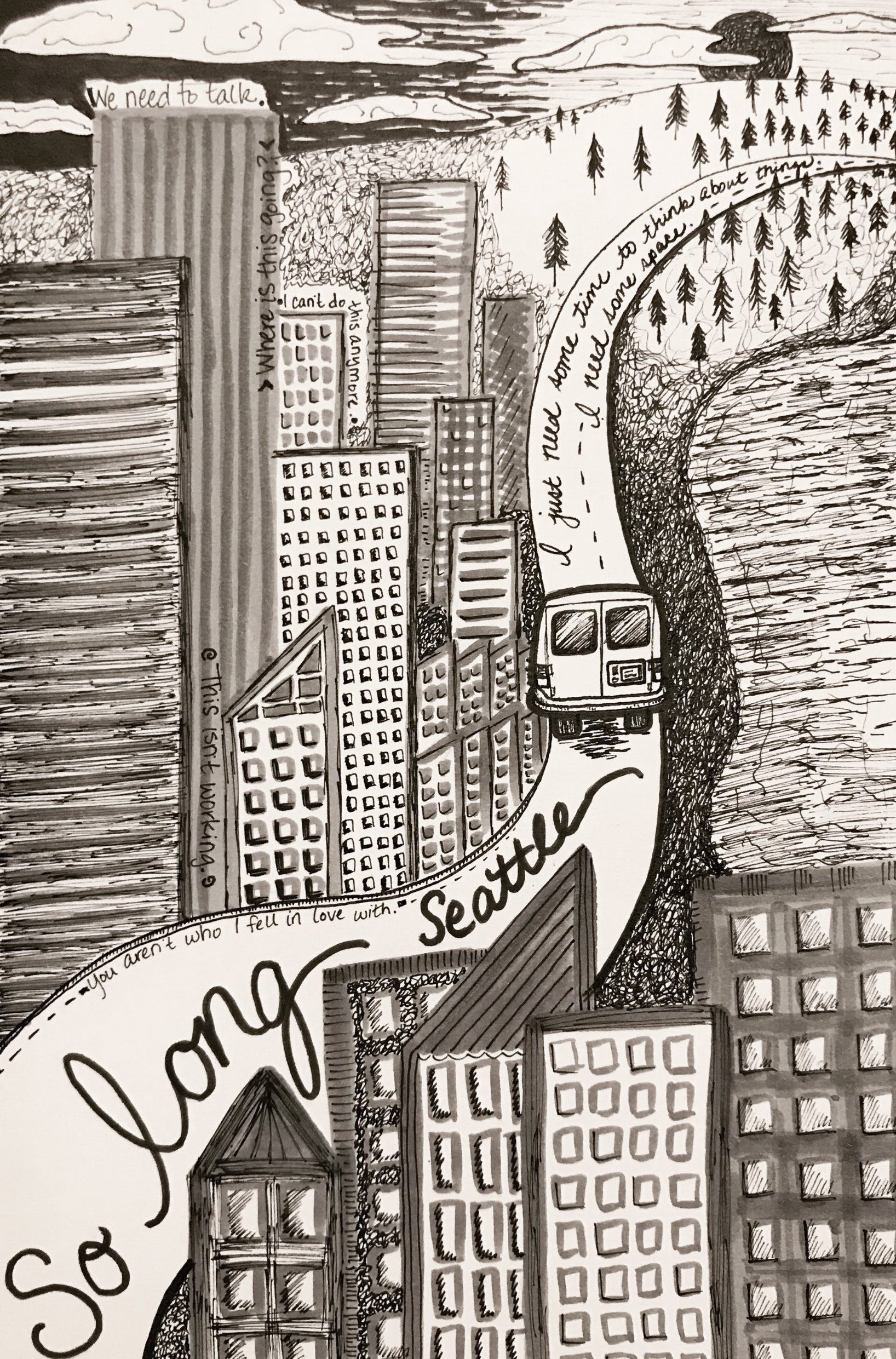

My studies will emphasize the use of pen-and-ink because that is my passion. My love for it is in some ways inexplicable because it’s so stark and high contrast and is the opposite of all of the soft, gentle flowing, colorful things that I crave and love. But Corot reminds me that it’s not the medium that evokes poetry or prose… it’s the spirit I bring into the application of my craft. So, because I resonate with his poetic spirit and want very much to draw poetry more than prose, I must trust that with practice I can convey such poetry with something as simple (and stark) as a black ink-pen.

Because I’m hoping to cultivate a relationship with a muse, I’m going to make that my main focus. But I’m thinking that drawing from cherished memories could be a great warmup exercise as I sit down at my desk each day. At this time, I’d like my muse to come from my current life instead of my memories. So I’ll be dipping into my memory bank for additional inspiration or for warm-ups to help me get loose and focused for the day’s work. (Also, I’m committed to reminding myself that any memory that should make it onto my page was never carefully studied for the purpose of artist-rendering (unlike Corot’s purposeful study of his subjects) and so I will be kind to myself when my memory-drawings inevitably turn out wonky and don’t look at all how they are in my head!)

I guess, in summary (and I’m saying this as much for myself as for you, dear reader, if you are in need of hearing it) - I’m imploring us to inject more heart into our art and less brain - to choose a subject we can let ourselves be captivated by and study at length, trusting that such a joyful fixation and disciplined approach will naturally let us grow in the technical skills that so worry us beginners and too often keep us from beginning.